Distinguished Alumni Award

I am honored to receive the Distinguished Alumni Award from the University of Utah’s College of Social and Behavioral Science and to share this incredible achievement with some heavy hitters!

Back in high school, I was a fiercely independent and rebellious teenager who resisted the idea of college. My passion was skiing, and I didn’t think a degree would benefit me. But my parents insisted, knowing I had the potential to make a positive impact on the world. While my heart was set on skiing, I also cared about air quality and climate change, yet felt clueless about making a difference.

Reluctantly, I applied to colleges and chose the University of Utah because it offered proximity to the slopes. Starting my undergraduate degree without a clear path, I ventured into intriguing subjects like gender studies, environmental science, the evolution of the human diet, and family economic issues. As I learned more, I developed a profound sense of purpose. I wanted to contribute to a better world, though completing a degree still seemed uncertain. I left some required classes for the final stretch.

In my senior year (which happened to be my 7th year at the U), a transformative class entered my life: American National Government with Professor Tim Chambless. He made his tests so difficult that you had to get extra credit to pass his class, earned by attending political forums at the Hinckley Institute of Politics. You would get even more extra credit if you asked a question.

I sat in the front row, soaking up the fascinating discussions. It was during this time that I discovered how government can be a powerful tool for problem-solving. Professor Chambless showed me how citizen activists can shape government and create the change they desire.

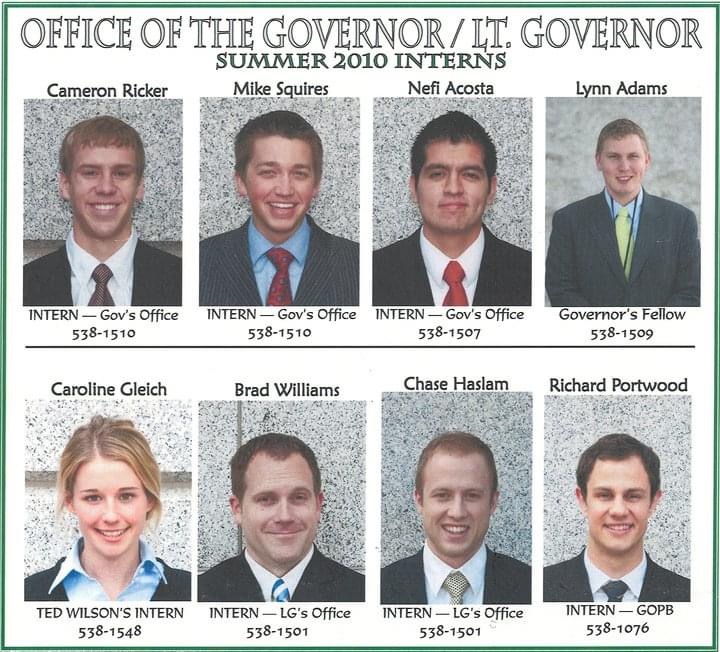

At the end of the semester, Professor Chambless urged me to apply for a Hinckley internship, and I took the leap. I had the incredible opportunity to work for Ted Wilson, Governor Gary Herbert’s environmental advisor and a legendary climber and outdoorsman who established the first ascent of the Great White Icicle in Little Cottonwood Canyon. That summer, I immersed myself in energy policy and outdoor access issues.

Under Ted’s guidance, I learned the value of taking a seat at the table. He entrusted me to lead meetings with influential figures in government. Ted taught me the art of finding common ground with those I disagreed with—a skill that has become invaluable in my life.

Thanks to the guidance of Ted, Professor Chambless, and many others at the U, I discovered my life’s purpose. I became an effective citizen activist, equipped with skills beyond what skiing alone could offer. Graduating with high honors and a B.S. in Anthropology, I merged my passions to create my dream job.

Since then, I’ve embarked on a global journey, fusing skiing, mountaineering, anthropology, and activism. I’ve influenced policy relating to climate and clean air at the local, state and federal levels. I see now how a college education transforms lives and I am eternally grateful to those who believed in me even when I doubted myself. To my parents, you were absolutely right—college was an incredible idea, and I can’t thank you enough for the gift of education.